1921-1957. — 41 photographs.

Biographical Sketch

Frank Stoll’s father, George Mitchell Stoll, arrived at Lake Saskatoon on June 20, 1910, along with his brother Charles. They had traveled over the Long Trail, via Grouard by ox team, coming into the area when the grass was lush and the wild flowers and fruit trees were coming into bloom along the creek. Having spent the previous few years as cowboys in the state of Montana, they decided their homesteads were ideal for the raising of livestock. A shack, barn and corrals were built of logs, some land broken and wild hay stacked that first summer, so they were prepared for winter. In 1916, with the arrival of the railway at Grande Prairie, Frank’s mother, Theresa Smith came from Toronto to visit her sister, Mrs. Percy Clubine. While here, she met and married George Stoll, never to return to Toronto again. The young couple moved into a new house built on the farm and George purchased his first horses to replace the oxen that had, till then, been the beasts of labour on the farm. The Stolls farmed in the Lake Saskatoon area for the next years. Four children were born to them: John in 1917, Frank in 1919, Majorie, 1921, and Aleda, 1926. Theresa passed away in 1937, and in 1939, Frank married Irene Bradley.

Scope and Content

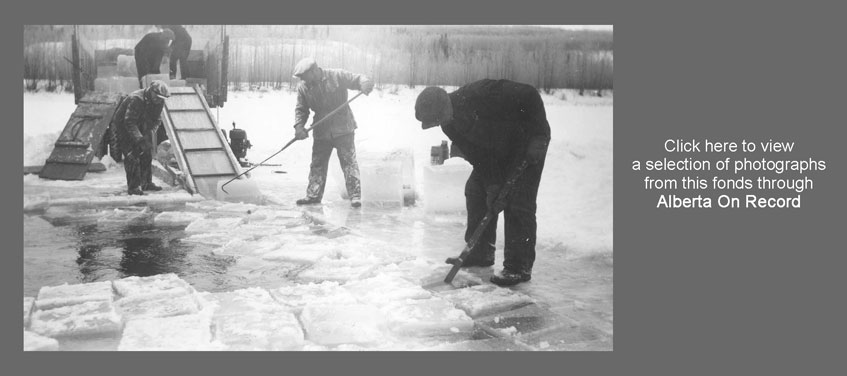

The fonds consists of 41 photographs showing Frank’s relationship to horses from his childhood to his own well-established farm, some photographs of an ice-cutting business he operated in the 1940s and some miscellaneous photographs of Pipestone Creek Store and a 1937 pack trip into the Rocky Mountains taken by students and teachers of Upper Canada College in Ontario.

Notes

Title based on the contents of the fonds.

Table of Contents

| Series 140.01 | Childhood and Youth |

| Series 140.02 | Marriage and Family |

| Series 140.03 | Ice-cutting Business |

| Series 140.04 | Miscellaneous |

| Series 140.01 | Childhood and Youth. — [1922-1940]. — 12 photographs. Frank was born in 1919. The first team of horses he remembers was Jess & Dolly, two of the first horses owned by George Stoll when he replaced his oxen with horses in 1916. They were just “Cayuses” or Indian ponies which had been brought into the country either by the native people who caught and broke them from bands of wild horses or by entrepreneurs who brought in herds of horses and cattle to sell to farmers and ranchers. Horses were used then for everything, not just for farming and transportation. Life was planned around how much work a horse could do in one day. Twenty miles a day of heavy pulling was the average workload. That was why stopping places were 20 miles apart on the trails. Horses worked a half-day, had a one to two hour rest, then were on again till six. It took six or seven horses to pull a two-bottom plow. After the plowing was done, the fields had to be harrowed, then cultivated or disced to prepare the seed bed, and finally seeded, all with the horses. Although many settlers used oxen in the early years, they were soon replaced by horses. Horses pulled cabooses through the pioneer trails; they freighted in unbelievable loads: the printing press for the first newspaper, the safes for early banks, even a large boat. They pulled the elevating grader which constructed the road and rail beds so that trains and vehicles could make their way into the country. Horses traveled those roads, and lesser trails, pulling dray wagons of freight to the railway and other destinations. On the farm Frank grew up on, there were up to thirty horses at one time. There were usually three six-horse teams to do the field work, and always brood mares raising replacement foals. Some of the neighbours brought in purebred stallions to improve the breed of their horses. The Craig brothers had a Clydesdale brought in from Scotland, and Percy Clubine had a Percheron brought in from Ontario. These horses were used for stud services throughout the district. A route was planned in spring for farmers who wanted to purchase stud services, and in early summer, the owner would travel with the stallion from farm to farm. Frank soon learned how to take care of the horses. They were fed three times a day, and in the winter four times. Every time they were harnessed up, each one was groomed and fitted to the harness, including the nose muzzle (or basket) which protected the horses from the nose fly. It took about an hour. Frank had to be up at 5:30 to do the chores, prepare the horses, have breakfast and be ready to go by 8:00. In the winter, the horses were kept in the barn and that meant the extra work of cleaning the barn. Then there was the vet work and blacksmithing shoes. Hooves had to be trimmed every 6-8 weeks, and shoes could only be left on 4-5 months, usually over winter. If the horses were used mostly for field work or traveling dirt roads they didn’t need shoes on all of their hooves—only the damaged ones. Then, the blacksmith would form corrective shoes to the individual hoof so that the horse could walk without difficulty. Frank’s uncle, Percy Clubine, was a registered seed grower and a well-known farmer in the Dimsdale area. The families worked and socialized together. Towards the end of the Depression (1937) the Stoll family bought a tractor, but the next year they couldn’t afford to buy gas for the tractor when time for fall work came around. Frank spent that fall batching on the “away from home” farm looking after the horses and doing the fall work. He used a team of 12 to pull a tractor-operated cultivator. The horses were turned out to pasture after the day’s work was done, and in the morning they were always at the far end of the pasture, not ready to start another grueling day. Usually one was easier to catch then the others, so Frank would catch that one and used it to herd the rest of them. Sometimes it took him almost all morning to get them all caught and harnessed. All of the hard work represented a savings of maybe $30 to $50 worth of fuel. The series consists of 12 photographs showing scenes from Frank’s childhood and youth, including farming activities. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Series 140.02 | Marriage and Family. — [1939-1955]. — 21 cm of textual records. On June 20, 1940, Frank married Irene Bradley and built a small home on his own quarter. Now he had his own horses. The Best Team was Maggie & Jessie, well-bred Clydesdales which looked and worked like the quality horses they were. Frank and Irene had two children: Bud, born in 1944 and Joan born in 1942. Even small children were safe with a good horse. By the time they were going to school, children would be able to ride and control their own horse. Bud and Joan had a school pony named Tiny Tim. The last real working team Frank had was Minnie & Maud, two Percheron Crosses, just after the war. Even though some of the farm work was now done with tractors, Frank liked the horses for doing winter work and for chores around the farm yard: hauling wood, cattle, feed for the cattle, manure from the barn. For a couple of winters they hauled the mail from Wembley, where the train dropped it off twice a week, to Pipestone Creek. In an emergency, when the roads were blown in or heavy with mud, the horses were able to go where the vehicles could not. Minnie & Maud could get the family into town even when the roads were impassable. Frank had one last team from the early 70s into the 80s—Floss and Fly. They belonged to the Campbells but stayed on the Stoll farm until they were old and stiff with age. Frank kept them until they were probably about 30 years old, but they didn’t have a harness on them for the last ten or fifteen years. Frank always liked to make his horses look good, with Scotch tops/collars and braided tails, and spreaders of red, white and blue rings on the harnesses. The fonds consists of 21 photographs showing scenes after Frank’s marriage to Irene Bradley, including their farm and children. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Series 140.03 | Ice-cutting Business. — [1947]. — 5 photographs. Before rural electrification came, people depended on the ice house to keep cream destined for the creamery sweet, food from spoiling and to provide good tasting water in the summer. The average ice house could hold about 100 blocks of ice 16” square by about 20” deep—enough to last the average family from April to October. It was either built with very thick walls or lined with sawdust to insulate the ice from the summer heat. Frank was about fourteen when he first started cutting ice with the long, heavy ice saw. An ice saw was about 5 ½ feet long with a heavy 8” blade and a T handle at one end. This handle was gripped by both hands and the blade rammed into the ice to start the cutting. It was difficult and time-consuming work, and he had lots of time to think about how he could build a machine that would do the work. In the early 1940s, Frank and his brother-in-law Bill Schmidt built an ice-cutting machine using a Mandrell Saw with belt and pulley, a Model A Motor, and a sawmill blade. Sixteen inches out from the saw blade was a smaller wheel which fit into the last groove for uniformly sized blocks. A loader was built from the feeder belt of a threshing machine and a small motor geared down so the belt didn’t go too fast, and run with chains so that it would not slip when wet. For the next fifteen years they were in the business of cutting ice, mostly for the surrounding farmers. Ice cutting started in January, when the ice was at least 16 inches thick. Most people liked to use lake water for cooling and river water for drinking. If it was really cold, hot water was put in the ice machine’s radiator to warm up the motor enough to get it started, or a fire was built under the motor to warm it up. The ice was scored to the depth the blade could cut—16 inches. You couldn’t hit water while cutting with the machine because then the blade simply shipped water instead of cutting. The job was then finished with the handsaw for the first row on each side, and after that the blocks were knocked loose. The loader was set at the edge of the hole with the lower end in the water. Blocks of ice were then guided to the loader with a homemade ice hook (made of a pitchfork handle and an iron rod bent at the end), picked up by the wooden slats on the loader and conveyed to the deck of the waiting farmer’s truck. In about an hour, Frank’s team could cut 700-1000 blocks of ice, 16 inches square by the depth of the ice (usually around 20 inches). The blocks usually weighed from 80-90 lbs each, but could weigh up to 200 lbs when the ice was three feet thick! The blocks were sold for 10 cents apiece. It took ten minutes to load a three-ton truck with 100 normal blocks, which would be the farmer’s summer supply of ice. In 1956, power arrived at the Stoll farm, and they didn’t cut any ice after that. The fonds consists of 5 photographs showing Frank’s ice-cutting business, which he operated in the 1940s. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Series 140.04 | Miscellaneous. — 3 photographs. Frank farmed in the Wembley area, near the community of Pipestone Creek. Pipestone Creek Store was where they picked up their mail. The Osborne Ranch was west of Pipestone, and it was from there that a party of students and professors from Upper Canada College set out on a trail ride into the Rocky Mountains. The fonds consists of 3 photographs showing the Pipestone Creek Store and a 1937 pack trip into the Rocky Mountains taken by students and teachers of Upper Canada College in Ontario. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||