Taste of History is a new limited-run blog series exploring some of the many old-school recipes and food culture found in archival collections. This time we will be making a classic dessert with a convoluted history.

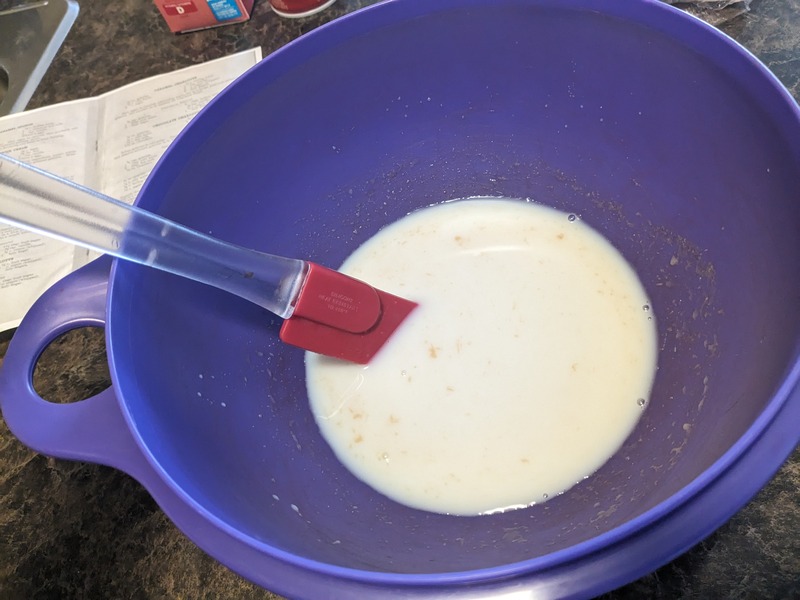

The recipe we tried this month is a dessert called the charlotte russe from 1933’s The Household Science Book of Recipes, edited by Annie L. Laird and Edna W. Park. This version of the recipe is primarily a flavoured custard filling with a crust of ladyfingers. The dessert though predates the recipe book by at least a hundred years and has undergone numerous transformations.

While many would look to the name as a hint to the origin of the recipe, in this case you would be lead on a wild goose chase. In modern recipes the etymology of the dessert has been variously tied to British or Russian royalty, the Old English word for custard (charlyt), and even a style of French hat. Unfortunately, as far as I could research none of these theory had significant evidence backing them.

Chef Marie-Antoine Carême, famous for his impact on 19th century French cuisine, claimed in his 1815 cook book to have invented the charlotte russe in 1803. Although he preferred to call it charlotte à la parisienne rather than charlotte à la russe. However, Maria Rundell’s written recipe for charlotte russe predates Carême’s through her 1808 book New System of Cookery. Further back in 1796 we also see the mention of a charlotte dessert in the poem The Hasty Pudding, written by Joel Barlow.

The dessert has also changed over the years in different cook books. Rundell’s version incorporates apples in the filling and uses stale white bread for the crust. The recipe we used in Household Science is similar to Carême’s, but later versions in the Southern United States substitute ladyfingers for yellow cake. A popular 1940’s New York version simplified the dessert as a piece of yellow cake sold in a paper cup topped with whipped cream and a maraschino cherry. Even after written recipes for the charlotte russe appeared, it has remained highly adaptable dessert.

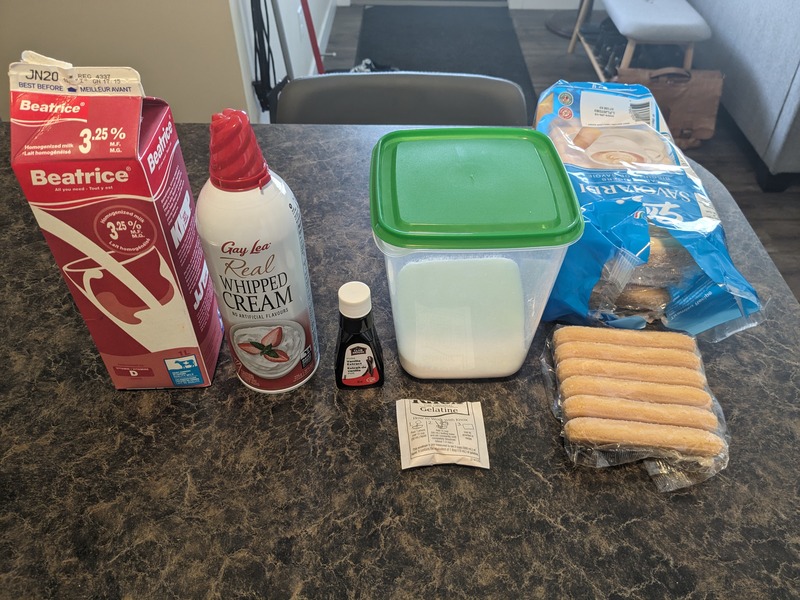

The first step of the recipe is preparing the 1/4 ounce of gelatin. The Household Science recipe likely used gelatin sheets, but what I had available was instant gelatin powder. After reconstitution the gelatin with 1/4 cup of water and dissolving it in 1/3 cup of hot milk I mixed in 1/3 cup of sugar and 1 ½ teaspoons of vanilla extract. The recipe actually specifies using fruit sugar or sucrose; unfortunately, I needed to employ a substitute and used standard white sugar (50% glucose, 50% sucrose).

Once all the sugar was dissolved in the mixture, I left it to partially set in the fridge and turned to the crust. In a round container, preferably a mould or spring-form pan, I lined the bottom and sides. I then returned to the cooled mixture and attempted to beat until foamy. The last step before pouring the filling over the ladyfingers was to incorporate the 2 cups of whipped cream. First a small portion of the whipped cream is also beaten into the mixture, but the remainder is then lightly folded in to keep it light and airy.

As shown in the photo at the top, the recipe did not go to plan. There were a few separate issues with my attempt, with the largest being the gelatin set significantly faster than expected. Rather folding in the whipped cream into a partially set mix to get a light and homogenous filling, the mixture was already too solid and unable to incorporate the cream.

The texture of the ladyfingers was also surprisingly uneven with some pieces being cake-soft and others tooth-shattering hard. Many modern recipes recommend dipping or brushing the ladyfingers in a flavoured liquid to ensure a consistent crust. While the texture of my charlotte russe fell short of the intended result, the flavour was pleasantly light vanilla that was not aggressively sugary.

Come back next month for a 1950s classic – molded salad.