Above photograph: H.P. Keith sitting in front of his tent, reading, ca. 1915 (SPRA 282.13, cropped from original)

Hindsight is 20/20, or so the old saying goes. Here are ten books about the Great War experience. Some are general histories while others delve into specific aspects of the war. The authors used a variety of documents to explore a wide range of ideas and topics related to the period. Most of these books are available at the Grande Prairie Public Library, and the call number is listed at the end of the title.

Canada’s Great War Album: Our Memories of the First World War

edited by Mark Collin Reid, Canada’s History Magazine, 940.371 CAN

This is an intensely beautiful book and not just because of the large collection of personal photographs and documents prominently displayed throughout. In 2012, Canada’s History Magazine called for contributions from the public for their stories and photographs about the Great War. Organized by topic, each chapter features an essay by an established historian, writer, or journalist, including Charlotte Gray, Tim Cook, and Peter Mansbridge along with accompanying images. While the book does provide a brief timeline of major events, this is really the story of the people who lived through this terrible conflict.

For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War

by Timothy C. Winegard, 940.3089 WIN

Timothy Winegard chose the word “Indian” carefully in this text. Noting that it was the common terminology of the time, used by Whites and Indians alike, Winegard also makes clear that this history does not include non-status Indians, Métis, or Inuit Canadians, all communities now contained within the terms Indigenous or Aboriginal. Nor does it include many status Indians who “snuck into” the army in the early days of the war or Indians from the Northern Territories. As he clearly lays out, Indians were not initially welcomed with open arms and when they finally were, they were carefully documented. But only status Indians. For this reason, Winegard limits his analysis to the experience of “Indians.”

Winegard explores the racism, acceptance, and mythology surrounding Indian soldiers and their shameful treatment upon their return home from the war. He does this with an examination of official documents and personal stories. The many images featured throughout help personalize the story of these men and certainly helped me to better visualize and conceptualize the contributions they made in the war effort. It also sheds light on the beginnings of Indian activism following the war. This book is highly recommended for anyone wanting a deeper understanding of both Canada’s role in the Great War and the conflicted relationship between White and Indian Canadians.

Three Day Road

by Joseph Boyden, FNMI BOY

The main narrative of this novel takes place after the war as a physically and spiritually wounded Xavier recounts his war experiences on a three-day healing journey. Xavier’s narrative shows two extreme reactions to the horrors of war: his growing dread and his friend Elijah’s growing relish for the death and destruction. The novel was inspired in part by real-life aboriginal World War I heroes Francis Pegahmagabow and John Shiwak.

In the course of the novel, Xavier’s aunt Niska recounts her own tale of the death and destruction of her way of life. I would highly recommend reading both For King and Kanata and Three Day Road for a better understanding of the war and its aftermath in Indigenous communities.

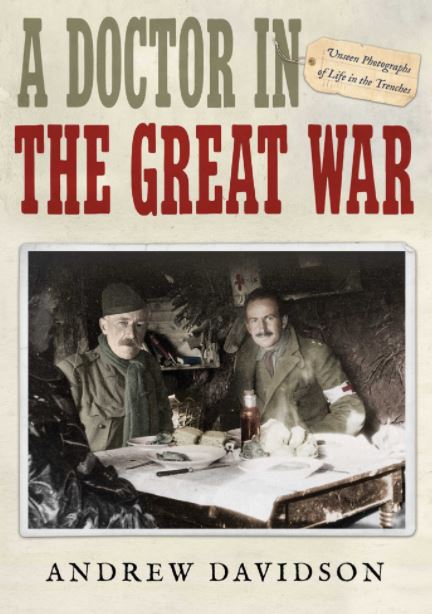

A Doctor in the Great War

by Andrew Davidson, 940.40092 DAV

Based on three photo albums left to the family by his grandfather, Andrew Davidson presents a beautiful written account of Dr. Frederick Davidson’s experience as a doctor in the British Army. Davidson never met his grandfather, who died shortly before his birth. Bequeathed the albums, along with a set of binoculars, Davidson was prodded for years by friends to do something with them. That something was this book. Lacking his grandfather’s personal testimony, beyond the photographs, Davidson turned to official government records, secondary sources, and published and unpublished memoirs, letters, and diaries, to piece together this beautifully crafted account of one man’s life in the Great War.

Of course, like any life story, it contains many life stories intersecting throughout and Davidson takes pains to include many anecdotes about the men his grandfather befriended. Along with the images, this is a very personal account of the war in the trenches through the eyes of a man not there to take lives but to save them.

The Wars

by Timothy Findley, CLA PB FIN

Written by thespian turned author, Timothy Findley, this is one of my favourite books. The narrative is told in first, second, and third person and moves back and forth in time as a historian tries to piece together the story of Robert Ross, a physically capable but emotionally scarred young man who enlists in the First World War. Ross, like many of his contemporaries, does not weather the war well, breaking down fatally and tragically. The novel examines the traumatic effect the war had on his already troubled psyche and challenges assumption and universality of military comradery. My favourite line in this book, which I’m going to paraphrase, comes from one of Ross’s friends while visiting him at his trench: “I retain the human right to be horrified by all that I see.”

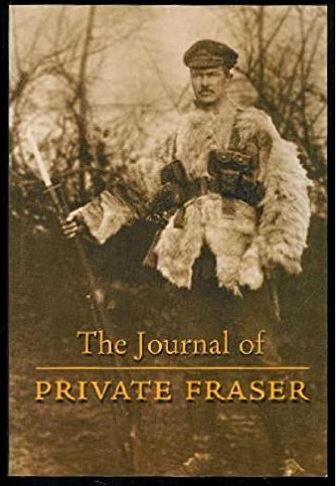

The Journal of Private Fraser, 1914-1918: Canadian Expeditionary Force

by Donald Fraser, 940.4817 FRA

Private Donald Fraser writes vividly of his wartime experiences in this war diary. Like most soldiers of the initial Canadian Expeditionary Force, Fraser was an immigrant who enlisted early to fight for King and country. He served until wounded at Passchendaele. This is a no-holds-barred first person account of training and life in the trenches.

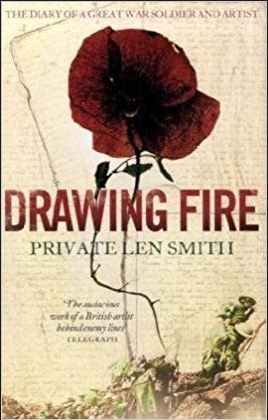

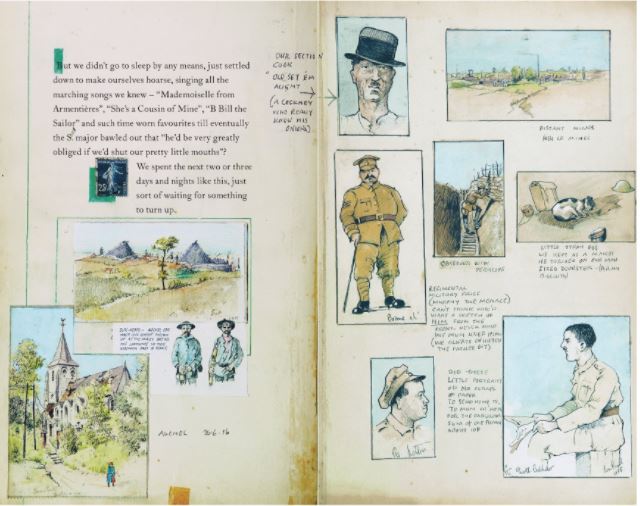

Drawing Fire: The Diary of a Great War Soldier and Artist

by Len Smith

Note: this book is not available through the library, but used copies can be purchased at reasonable prices through Bookfinder or AbeBooks and it is a worthy addition to your personal collection – too good to miss!

This is probably one of the most beautiful books I have ever read. Illustrated by Len Smith, a British soldier and artist, the book features exact reproductions of his handwritten memoirs. Most of the handwriting is replaced by a regular font but some pages are reproduced in the original to get a feel for his style of writing. The book is interspersed with Len’s original drawings and memorabilia.

Len kept his diary on scraps of papers hidden in his pants, which he later collected and wrote out in long hand. Len notes in his introduction that he made no corrections or additions, wanting the reader to feel the immediacy of his original words. And you do. With his sense of humour and his generous understanding of the emotional toll on his fellow soldiers, Len comes across as a gentle and practical person. He was also ingenious, as his artwork sprinkled throughout and accounts of creative endeavours for the war effort will testify. My favourite inventions are the two-yard panoramic map of the enemy troop lines at Vimy Ridge which he created while dodging front-line enemy fire; and the fake, hollow spy tree. Len had crawled within yards of the enemy line to draw a real dead tree in exact detail. He recreated the tree with stairs inside and a window for the observers. During the night, the real tree was removed and the fake tree installed, along with an underground tunnel leading to the tree.

What Len has produced here is nothing short of miraculous and it is baffling that he is so relatively unknown and undecorated. The best way to rectify this injustice is to read this book.

In Fear of the Barbed Wired Fence: Canada’s First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1920

by Lubomyr Luciuk, 940.31771 LUC or read it online

While Canadians were fighting the good fight for democracy overseas, fear led to some very undemocratic activity against one particular group of Canadians. Luciuk illuminates this dark chapter of Canada’s war experience largely through the judicious use of photographs, letters, newspaper clippings and official documents. The actually text in the book is fairly brief, with the images and the footnotes taking up the bulk of the book. The footnotes, however, pack a lot of informational punch. For me, the most telling testament of the prejudice of the time occurs on page 98: “… as many as 10,000 Ukrainian Canadians volunteered for service…From among the Canadian volunteers, all men with German names were, on orders received from the War Office, placed under arrest…” This seems like duplicity of the worst kind. I highly recommend this book for anyone wanting to understand how fear compromises our democratic ideals.

First World War for Dummies

by Dr. Seán Lang, 940.4 LAN

I guess there really is a Dummies book for everything. For those of us who are chronologically challenged, this is a great starter book. It is based on the British and European experience, but it lays out concisely and in an easy to follow format the events and issues leading up to the war, social changes during the war, the experience of women and civilians, the aftermath, and finally, how we remember the war. The book is text heavy but still an easy read. The format lends itself to quick dives in and out so it doesn’t feel overwhelming. The last chapter includes four top ten lists for generals (including our very own Sir Arthur Currie), films, wartime writers, and enlightening places to visit.

Clio’s Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars

by Tim Cook, 940.41271 COO; and “The Great War, Archives, and Modern Memory,” Archivaria 46, by Robert McIntosh

Okay, I’m fudging a bit here on the book part. Cook’s book examines the why and how of what we know about both World Wars. The first two chapters of this book are relevant to the First War. They explain the great chain of activity set in motion largely by two men – Sir Arthur Doughty, First Dominion Archivist, and Max Aitken, First Baron of Beaverbrook – that led to the intense document creation and collection researchers rely on today to study the Great War. Cook’s book places more emphasis on Aitken’s contribution to our military documentary heritage while McIntosh’s essay gives both men fairly equal weight. Besides helping us to understand the fluid role of archivists, document creation, and historical activity, these two works also help us to understand why and how World War I helped forge our distinct Canadian identity.

On a side note, McIntosh writes absolutely the best sentence to sum up the Great War: “The war’s most immediate consequence was mass bereavement.”

Lest we forget.