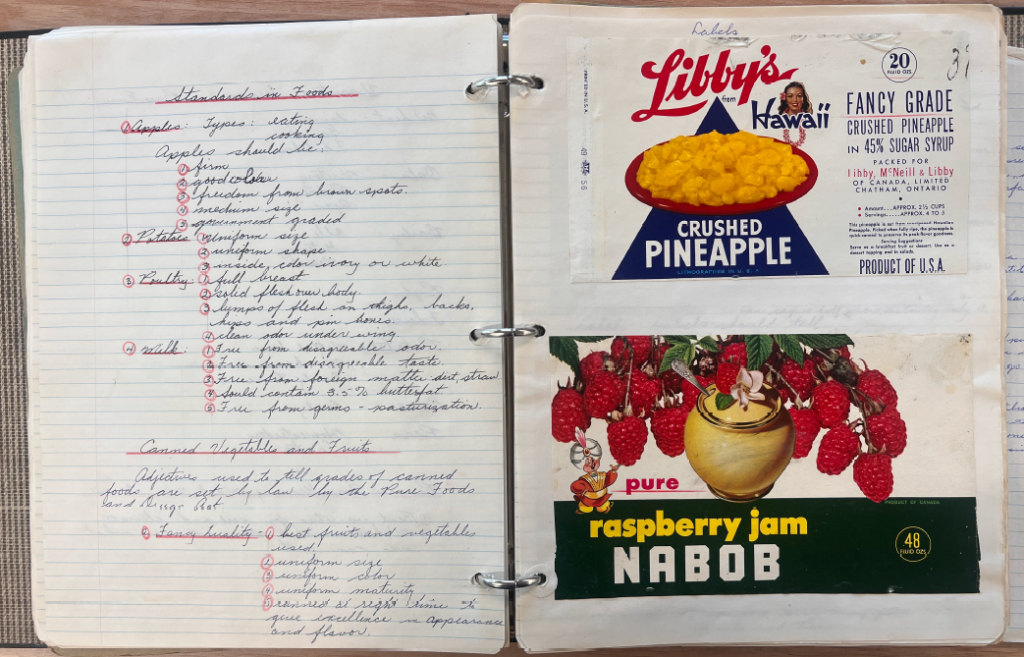

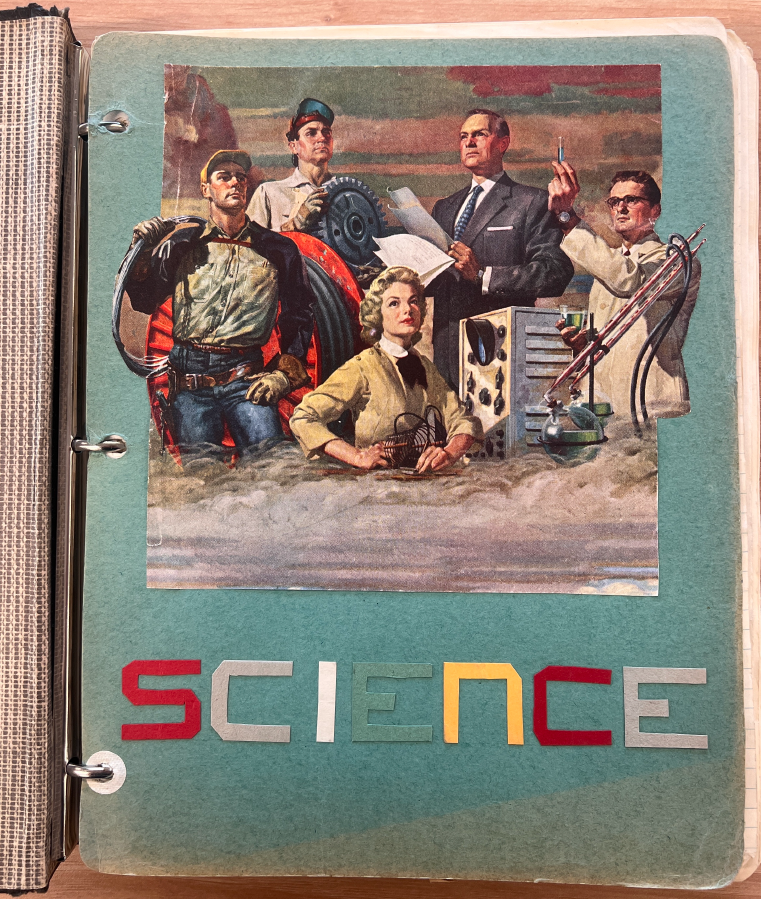

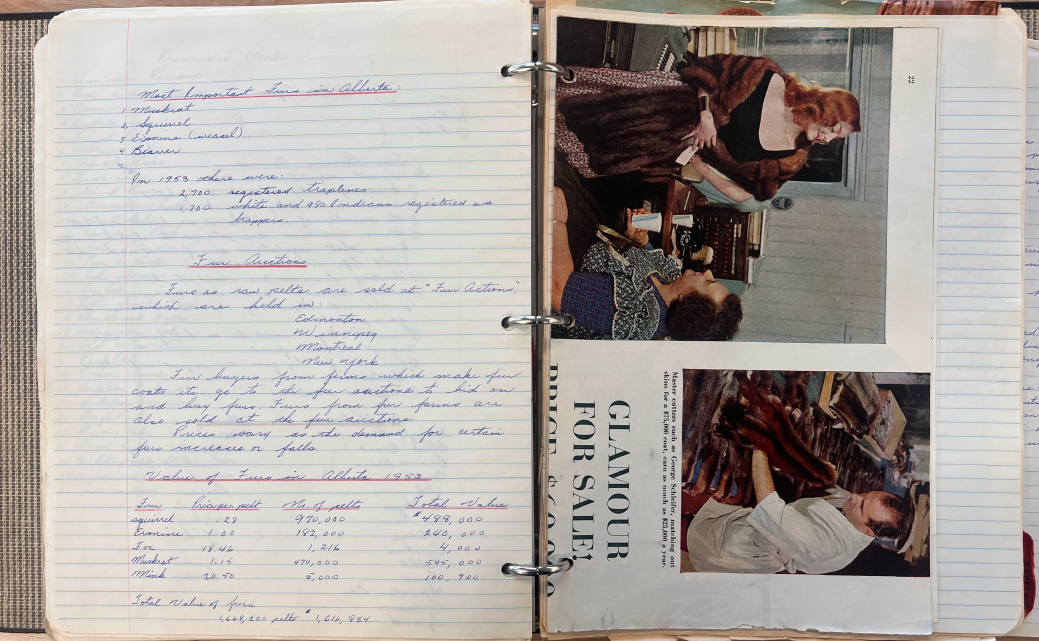

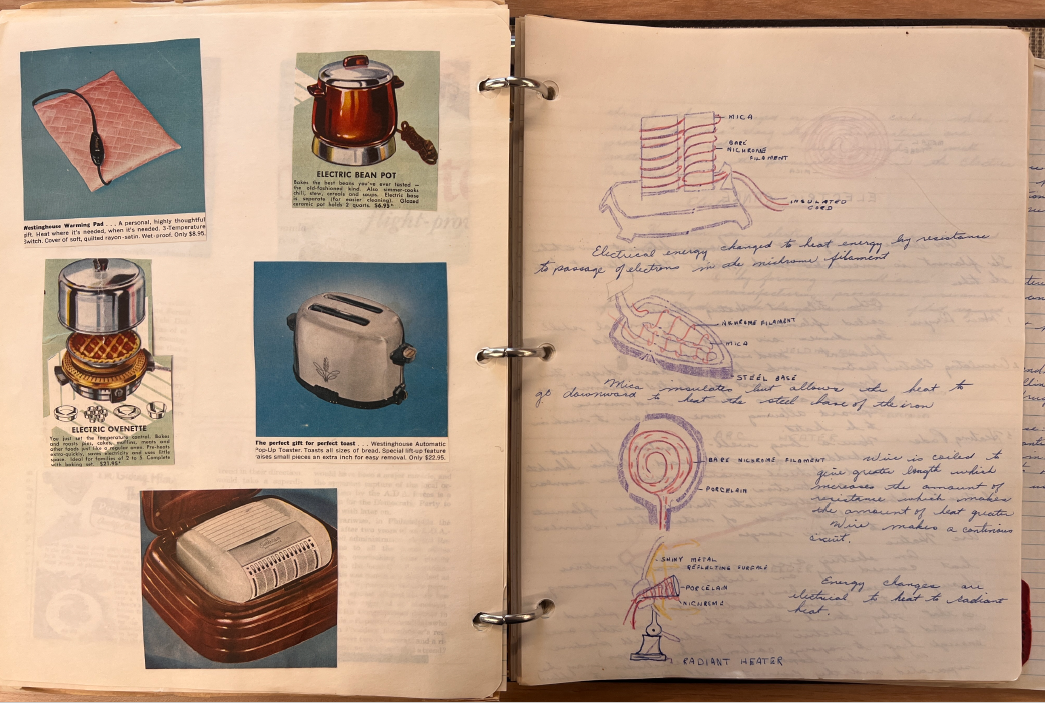

One of my favourite finds at the SPRA was one teacher’s binder holding materials for teaching science, likely created in the 1960s. On the first page in the binder, its subject matter—”science”—is spelled out from letters cut from construction paper, and a colourful picture cut from a magazine provides an illustration (see fig. 1). The picture brings together heroic-looking figures who each personify a different kind of work, from electrical and mechanical work to bench science and paperwork. Subsequent pages cover a wide range of topics, from vegetation and nutrition to genetics and electricity, and also include assorted clippings from newspapers, magazines, and other sources, including labels from food packaging (see image at the top), an article about fur coats (fig. 3), and advertisements for electrical appliances (fig. 4). Teresa Dyck, Access Coordinator at the Archives, helped me identify the binder’s maker as teacher Karen Burgess, who spent 11 years of her retirement (from 2002 to 2013) working at the Archives, where some of her work would have also involved collecting and organizing clippings from various sources, just as she had done for her science binder.

My research on 20th-century schoolteachers like Burgess and Hanson has shown that repurposing clippings from magazines and newspapers for teaching was a widespread practice. Most teachers were making do with few available resources, and so they had to be resourceful when developing lesson plans. But this practice also aligns with a progressive approach to education that was adopted in Alberta in 1935. One of the hallmarks of this approach was “Enterprise education,” which emphasized practical hands-on projects rooted in themes related to everyday life. Popular themes included “how we get our food,” “we visit the farm,” and “we visit Holland,” and teachers worked with their students to develop activities that brought the theme to life in the classroom. As historian Amy Von Heyking explained, the purpose was to hone “students’ research and problem-solving skills,” and so “no textbooks were specifically authorized or developed for the new program.” Instead, teachers and students were encouraged to seek out their own resources in current magazines and periodicals, through audiovisual resources like movies and slideshows (some of which were available through the University of Alberta’s Department of Extension), and by appealing to local businesses. Though not prepared for the purpose of Enterprise teaching, Burgess’s science binder shares in this approach by repurposing popular imagery for educational purposes.

Another highlight from my time spent at the SPRA was learning about one expert in Enterprise education, schoolteacher Edna Moyer. Moyer began her teaching career as Edna Small in 1918, in a one-room school in Czar, Alberta. From 1920 to 1969, Moyer worked in various schools across the County of Grande Prairie. In 1954, Moyer taught a course on “Social Studies and Community Problems” for the teacher training program at the University of Alberta. The letter offering her the position, now in the SPRA, explains that “the core of the course, Education 106, is really the Enterprise—how to select, organize, develop and evaluate it.” As a grade five teacher at Montrose School in Grande Prairie, Moyer had recently organized an Enterprise project on Alberta’s resources and products, a project that was repeated at the Swanavon School in 1962, where Moyer was principal. A newspaper article that documented the resulting exhibit held at the Swanavon School, now also in the SPRA, described how the “enthusiasm of the youngsters throughout the school year in ‘discovering’ Alberta, its history, its resources and its economic expansion, resulted in a display of hundreds of its products” (figs. 5 and 6) The article lists 59 businesses in Alberta that contributed to the exhibit, and quotes Moyer expressing her gratitude to these companies “for their support and cooperation.” Moyer went on to explain that “our Grade 5 class has had a lesson in learning its Alberta products and resources better than any text book could give, and one the children who participated will never forget.” This, of course, was the logic of the Enterprise. Instead of giving students a series of facts to learn, Moyer encouraged students to seek out their own resources and adapt their learning to those local resources.

Today’s teachers will recognize both Burgess’s and Moyer’s strategies for teaching, though available resources have changed so that magazines and newspapers are replaced by websites and the cutting-and-pasting of paper collage is replaced by digital cut-and-paste and slideshows. Looking closely at the records left behind by Burgess, Moyer, and many other schoolteachers across Alberta calls attention to the creativity and care required to source materials and create something new out of them. In some ways, their work was a lot like the work of archivists, who also carefully collect, organize, and preserve records that will serve a future generation. These teachers were also a lot like artists, who create new meanings out of the stuff of everyday life.

References

Burgess, Karen. “Science” Binder. South Peace Regional Archives, General Curriculum Reference File, SubSeries 510.07.042.

Gordon and Edna Moyer Fonds (1911-2015). South Peace Regional Archives, Fonds 422.

Swanavon School Reference File. South Peace Regional Archives, SubSeries 510.07.248.

“Transitions at the Archives.” Telling Our Stories 4, no. 3 (June 1, 2013): 20-21.

Von Heyking, Amy. “Implementing Progressive Education in Alberta’s Rural Schools.” Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation 24, no. 1 (2012): 93–111. (Quote is from page 97.)